Why are people obsessed with dubious personality tests?

Issue 2: Why people love dodgy personality tests, interventions to reduce emissions and recidivism, and replacing university administrators with AI.

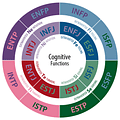

Scientists love to hate on the Myers-Briggs Personality Test, easily the most popular and well-known measure of personality. For good reasons. As explained in this recent article by Laith Al-Shawaf, experts believe that the Meyers-Briggs has dubious predictive ability and is grounded in debunked theory. To make matters worse, it’s unreliable. Which mean…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Power of Us to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.